In 2022, for the first time ever, ultra-wealthy spending on elections topped $1 billion.

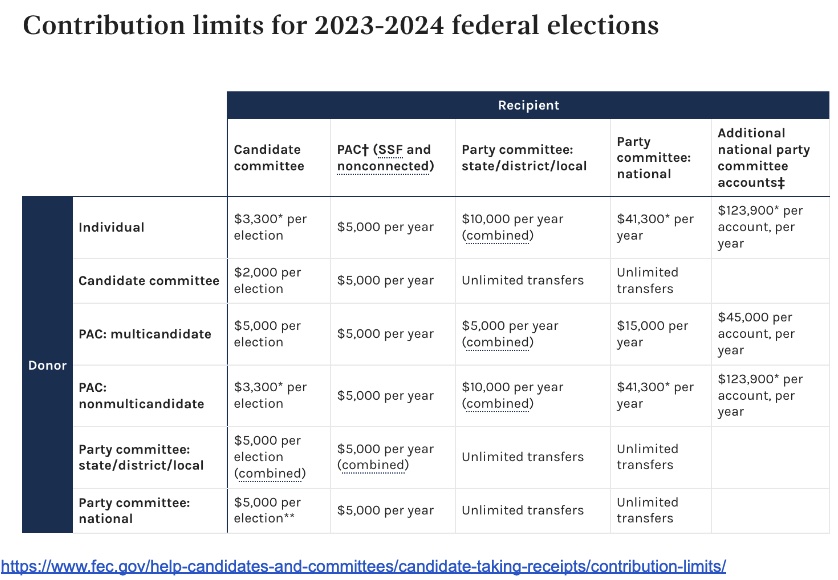

If you’ve ever donated to a political campaign, you may have seen a disclaimer on the donation form noting that contributions are limited to somewhere between just a few hundred dollars and $36,400, depending on the office the candidate is running for. There are very strict limits on what a person or group can donate directly to a candidate, campaign, or party. Here’s a breakdown of the federal limits:

And California’s state and local candidates vary by office and jurisdiction. You can find them here!

Expenditure limits are incredibly important to ensuring that politicians aren’t unduly influenced by people with access to unlimited funds. But if such limits exist, how did corporations and the 1% spend more than $1 billion on the 2022 election?

To answer that question, we have to go back to a 2010 Supreme Court decision, Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission. The Supreme Court ruled that a long-standing ban on corporations spending money on elections violated the First Amendment. The ruling, combined with several other court cases and changes in election law, paved the way for unlimited “dark money” in our elections.

Here’s how it works: When you or I donate more than $50 to a campaign, not only are we limited in what we are allowed to give, the campaign is also required to report our names to bodies overseeing the election. These requirements keep campaigns transparent and honest as to who is supporting candidates and how much they are giving, so that way the public can know critical information before voting for them.

But corporations and billionaires can make an end-run around these laws, and here’s how. You may have heard of the term “PAC” before. PAC stands for “political action committee,” and they operate in two ways: either by giving directly to a candidate within the limits we talked about earlier, or doing their own campaigning, called independent expenditures which does not have any contribution limits so long as it does not coordinate with candidate campaigns (you may have seen ads on television with disclaimers like, “This ad is paid for by XYZ Committee and is not connected to any candidate.”). A Super PAC runs its own campaigns.

PACs do have to disclose their donors, but the reporting requirements provide ways for the committees to conceal their donors, and there is no limit to how much money can be donated. So corporations can create a non-political entity to pool their money and then donate to PACs under that group name, hiding who the actual funders really are. That’s why some Super PAC funding is often called “dark money.”

This “dark money” loophole is how Uber and Lyft were able to create Issue Committees (a form of a State PAC to campaign on ballot initiatives) to pour $200 million into defeating Proposition 22 in California in 2020. It is what allowed an anonymous Republican to give an eye-popping $1.6 billion to a group controlled by political operative Leonard Leo, who distributed the money, among other races, to dozens of efforts to put conservative justices in federal judgeships. Similar groups spent more than $40 million in just 3 months on California’s Assembly and Senate races in 2022. And they spent more than $20 million on the California U.S. Senate primary alone.

Of course, you and I can donate to PACs, just like that anonymous donor or Uber and Lyft did. But as long as these donations can be limitless, rich corporations will always be able to have an outsized influence on election outcomes and exert more power over legislators than the everyday public. As long as these donations can be anonymous, we cannot hold them accountable for the policies they are trying to influence, and the public doesn’t know who or what they are really voting for.