How do you sustain political activism and optimistic energy over the whole of your life?

It helps to have a long view.

Of course, if you are 77 like me, it’s easier when you don’t forget what you lived through. And maybe it will help you, to look alongside my last 65 years, setbacks and progress, to help build your own worldview that will sustain decades of progressive activism and energy. This view includes both the negatives and positives of the moment — it doesn’t presume success for any side. It understands the dynamics of change and the forces lined up on each side. And it allows you to pick the place to work and the actions you think will be most effective in our push for progress.

Whether you are part of a movement’s success or a setback, you should seek to understand why things turned out the way they did. Take a historical perspective to the events you are living — and take action with this knowledge. If your goals are further away than allowed by the present world, find interim objectives, don’t abandon the long-range goals, but instead focus on earlier steps to move us in the right direction.

My activism started in 1955, the year Emmett Till was murdered. I was 12 then, the only child of a family of very progressive parents and grandparents (let’s call them Reds). My father had been a lifelong union organizer and was now working as a home builder in Orange County, and so, while my mother would not move there, we got close: Downey, California. There I was, a 12-year-old Jewish socialist Red, in the heart of a conservative community.

My first overt political act was to turn down the American Legion Award, granted to me for outstanding citizenship. In the wake of Emmett Till’s murder, by rejecting the award, I attempted to draw attention to the role the Legion was playing in promoting a view that America was without significant flaws, ignoring its history of Native American genocide and slavery, Jim Crow laws, and segregation.

This act was a highly instructive experience for me and formed an underlying foundation for my optimism because I was instructed by my father’s union experience, which started with respecting the people he was trying to organize and accepting whatever they thought when he met them. Our organizing philosophy was to listen, ask questions, and try to remember that family backgrounds are mostly what shape peoples’ views of the world. The lesson I quickly learned was that few people had the opportunity to grow up in a family like mine, and following that realization, I felt obligated to share what I knew and use that knowledge to bring people together with the goal of moving people to act for progress.

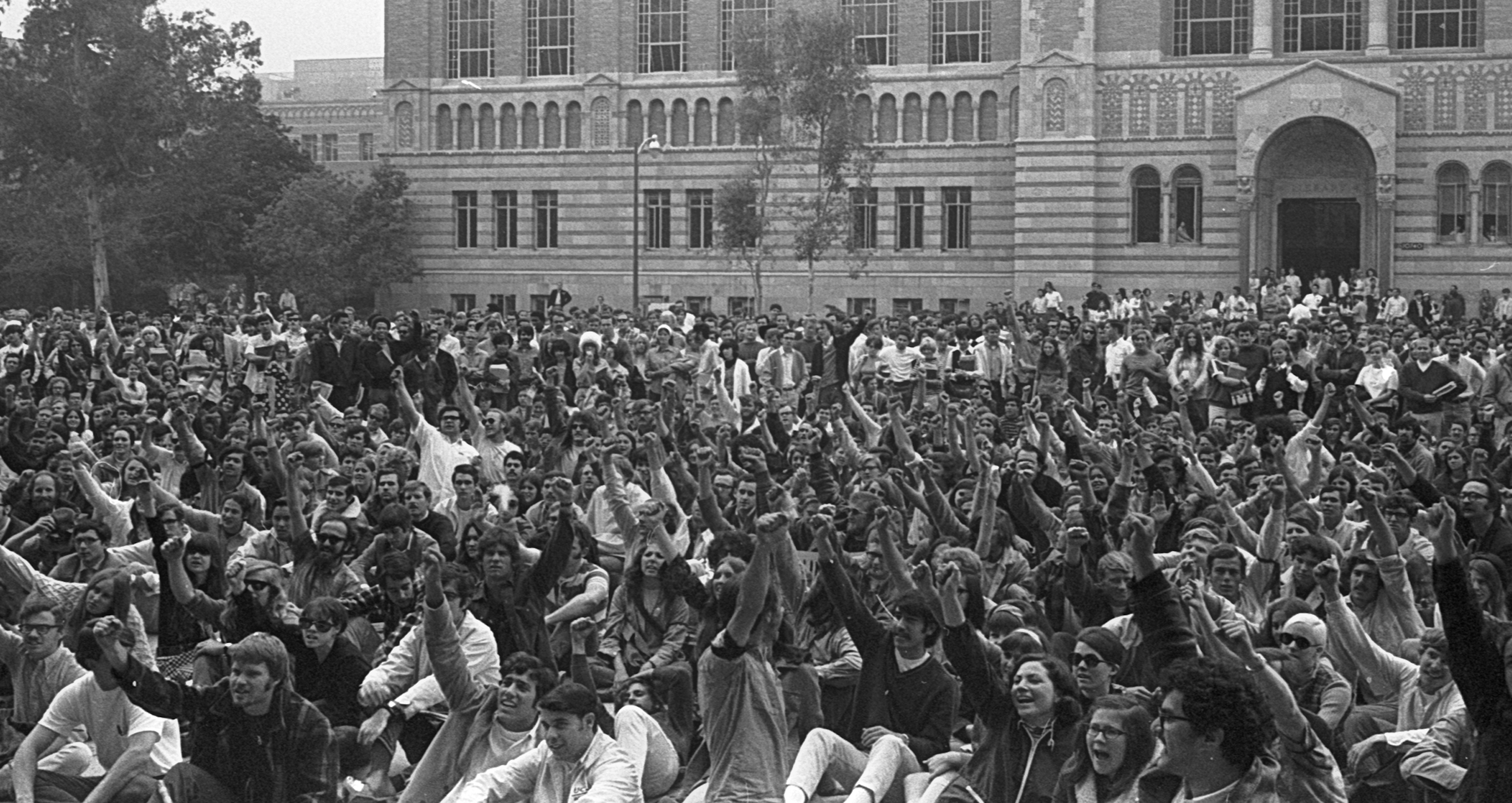

By high school graduation in 1961, I had participated with hundreds of students in political actions and forums. In the next 25 years, as the result of street demonstrations, marches, and countless other actions, we made incremental progress, and much changed for the better. But over the years we learned how much work still needed to be done.

The mid-sixties saw the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act passed into law.

The early seventies saw mistrust from the government lying about Vietnam, which led to antigovernment sentiment and paved the path for cutting the government’s budget, also known as tax cuts, which spurred income and wealth inequality to levels not witnessed since the late 1920s.

As the income and wealth gap grew, other efforts to diminish social progress began to pick up steam as well, such as the War on Drugs and mass incarceration. But progress was still being made in other areas of American life — LGBTQIA+ rights expanded from the right to marry to the inclusion of transgender rights and the expansion of LGBTQIA+ job-security protections under federal law. Today, we are nowhere near an equitable and just society, but way ahead of 2010, and way, way ahead of 1955.

Now it’s your generation’s turn to pick up the baton and push us even further toward our vision of a truly equitable and just society.

Most people who join the struggle for progress do so out of necessity. If you are one of those people, perhaps my experience can help shape your work to be more effective and your spirit sustained by this longer view. If you have more choices to pick your struggles, accept that it is a privilege to be able to participate.

My advice to you: look at the complexities and unpredictableness of the world and resolve to find the best place to spend your time, talents, and energy to maximize our progressive movement, accept setbacks as learning time, and realize that as long as we may live, there will be challenges to our society and a world to make better.

Keep your head in the game and have a long view. Setbacks may come, but with courage and purpose — progress can and will be made.

Jim Berland, a Courage California Institute member, authored this blog. Photo credits are also attributed to Mr. Berland.